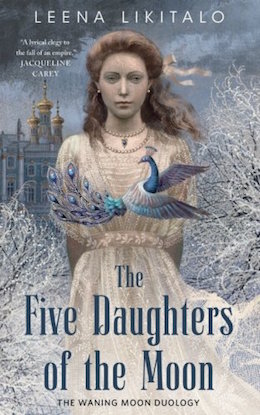

First in a duet from Leena Likitalo, The Five Daughters of the Moon is a second-world fantasy inspired by the Russian Revolution. The narrative follows the five sisters of the royal family as their empire collapses around them, driven in part by youthful idealism and in part by cruel magic and manipulation. Each chapter is told from the point of view of a different sister, from the youngest Alina who sees the world of shadows to the oldest Celestia who has become involved with the scientist-sorcerer Gagargi Prataslav.

Representing the revolution from the interior of the royal family, Likitalo is able to explore a range of reactions and levels of awareness; Elise and Celestia are aware of the suffering in their empire and wish to support a revolution that will address it, while the younger three are more aware of the horrible magic and undercurrents of betrayal surrounding Prataslav, but no one will listen to their concerns. This mismatch leads to the beginning of the collapse of the empire itself.

Likitalo’s reinterpretation of the Russian revolution is contemplative and straightforward. The interior lives of the narrating characters are equally as significant as the action occurring around them; each of these girls has a specific outlook and set of blind-spots, and the novel does a solid job of representing them all concurrently. It’s also intriguing to see a full royal lineage decided by and reliant on female succession: the Empress chooses lovers to bear children from, but those fathers change from child to child and the royal family is entirely made up of daughters.

There are, in truth, only two significant male characters: Gagargi Prataslav (the Rasputin analogue) and Captain Janlav. The gagargi is the villain of the piece, whose Great Thinking Machine runs on stolen human souls, while the Captain is a young idealist whose romance with Elise is manipulated and then erased from his mind by the gagargi. I’ll be interested to see his role in the second half of the story, as Likitalo is hinting quite forcefully that his lost memories might be recoverable and significant.

The book’s focus on girls’ lives, strengths, and weaknesses makes for a fresh take on the question of violent revolution. Most of these girls are too young to participate fully but are nonetheless caught up in the struggle. Sibilia, fifteen and on the cusp of her debut, is one of the most interesting narrators as a result of this duality. She is both too young to be an adult and too old to be a child. Her chapters, also, are directly recorded as if to her notebook—she is the only one of the five to keep a written record. She observes and analyzes, and believes herself to be an accurate narrator, but when we contrast her observations with those of her older sisters we realize that she is still on the edge of childhood and misses quite a lot. It’s a clever and subtle contrast that adds depth to the otherwise-direct narrative.

The novel’s concern with interiority also has the curious and pleasing effect of rendering the reader as blind and acted-upon as the characters. There are large-scale events happening in the world around them, but the daughters are limited to their observations—first within their gilded palace and then from the blocked windows of the train carrying them to exile or worse. The shift from the narration of Merile, eleven, to Celestia and Elise, twenty-two and sixteen, is notable as well for different reasons: the older girls are aware of the real dangers of the men and the world around them.

Likitalo doesn’t shy away from the physical reality of being a young woman in the world, even in a world where women are treated more as equals. Celestia is ensnared and raped under the influence of magic by Prataslav; she trades her unwanted unborn child to a witch for the healing of her youngest sister. It is an almost-unspoken knowledge that the oldest children choose to keep from the youngest, who have not yet had to think about the real possibility of violence against their bodies. This multifaceted approach allows The Five Daughters of the Moon to explore issues associated with womanhood and femininity in a thorough and understated manner, full of women and girls as its story is. Given that this is a story inspired by the 1917 revolution—a revolution often associated primarily with men, where the women are merely victims (the girl children, the most famous of whom is Anastasia) or fall prey to bad influence (Tsarina Alexandra)—it’s especially intriguing to see it reinterpreted and approached entirely from a female perspective.

As for criticisms, I admit to a measure of confusion at the decision to split this arc into two short novels and publish them as such. While I’m comfortable with books that do not stand on their own, as well as duologies that lean heavily on each other, in this particular case the narrative feels clipped and unbalanced by it. The development in the first volume unfolds at a measured pace; the majority of the second half takes place on a train during the sisters’ captivity. The climactic scene, of Celestia’s rescue plot failing, feels like the middle scene of a book building tension for the following chapter. The slow development of the plot arc contributes to the sense of imbalance or abruptness in the close of this volume.

Of course, I’m still very interested in seeing the second half of the story—but it’s hard to think of it as a second novel. The Five Daughters of the Moon does not stand on its own, and the pacing is a bit off-putting as a result, but the narrative itself is nonetheless compelling. I strongly suspect that reading it back to back with its companion novel will erase most of this sense of mismatched pacing; unfortunately, we’ll have to wait and see for that second half to be released.

The Five Daughters of the Moon is available now from Tor.com Publishing.

Book two in the Waning Moon duology, The Sisters of the Crescent Empress, publishes November 7th.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.